Mastering Hieroglyphs: III. The Language of Death

The Philosophy of Dying in Ancient Egyptian Mortuary Texts

Any mastery of Hieroglyphs starts with understanding the correlation between language, symbols and their multiple facets of meaning, and it is the language of death where this sacred connection becomes the most apparent.

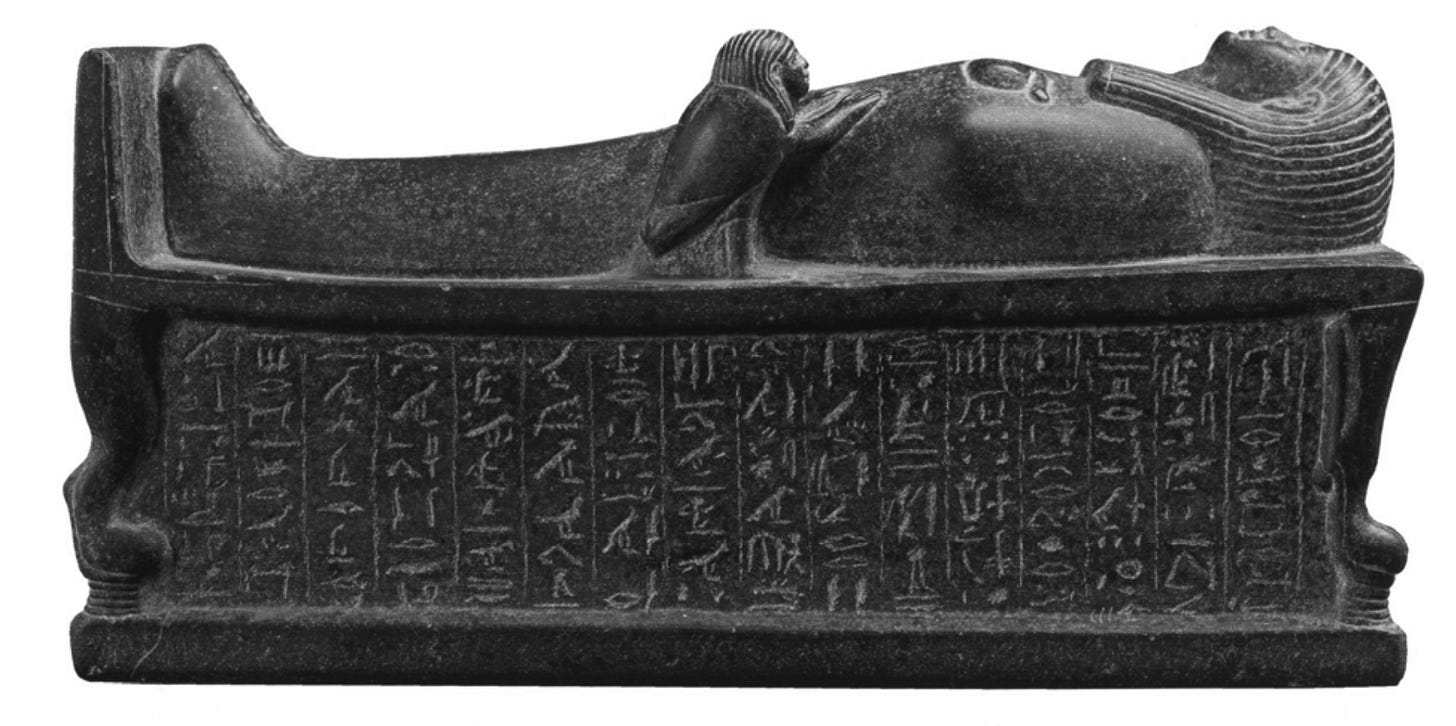

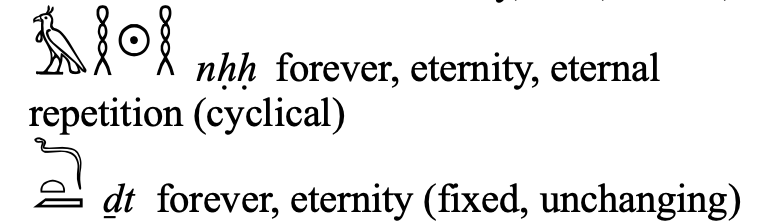

From the example of Egypt, we have seen how death can be imagined and experienced in the framework of a cosmotheistic religion. There is, first of all, the “symbiotic” aspect of death, which emerges most clearly in the image of death as return. With the act of being placed in the coffin and buried, the deceased enters the womb of the Great Mother, the sky- goddess: all life comes from her, and in her body, the deceased is rejuvenated in the eternal cycle of life, on the model of the sun. In this way, death is integrated into a superordinate concept of life that finds renewal, not an end, in death. For the Egyptians, death was a passage to a continuation of life, though in an altered state. Even gods died, and this fact in no way contradicted the Egyptian concepts of divinity and immortality. Dying, they did not withdraw from the cosmic symbiosis. That even the gods could die did not mean that they were finite. Cosmic life was an interaction of the unchanging duration of Osiris and the ceaseless renewal of Re. (J. Assmann, Death & Salvation in Ancient Egypt; p. 408)

Ancient Egyptian Words for Death

Author’s note: This is an elementary vocabulary and reading lesson and at the end of this - rather long - dictionary raid you will not only be able to safely return from the afterlife but also to handle long words written in Hieroglyphic script.

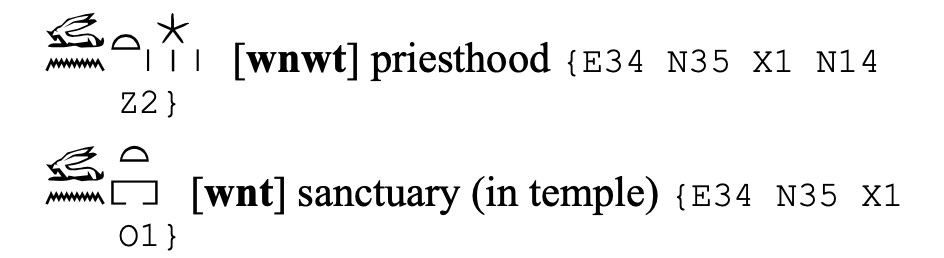

All signs are listed with their Gardiner classification number: i.e. A14 etc. - and all Hieroglyphic words are followed by a simplified transcription in brackets for pronunciation. Reminder: X is a strong Klingon “KH” (see explanation below); capital D and T are pronounced with a “DJ”/”TJ” sound, W is “OU”; when there is no vowel written an E sound is added between consonants.

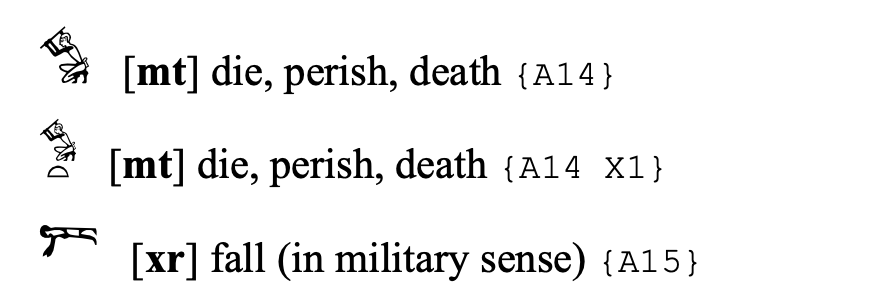

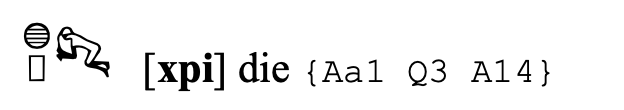

The first Hieroglyph 𓀐 depicts a “man with blood streaming from his head” (Gardiner Sign A14), has a variation of 𓀑 “man with an axe to his head” and is pronounced MET or MUT/MWT. This is one of the most basic words for death, which is often used in non-mortuary contexts to describe the killing of enemies and animals. It also morphed into the Hieratic sign that looks like a stick 𓏱 (see Z6 below), which then became a determinative used in other words to denote dying or death.

Here death is written with the biliteral sign of “spine with fluid” 𓄫spelling AW and the Hieratic version of “the man with blood streaming from his head” while the little spiral in the middle spells the letter W pronounced U.

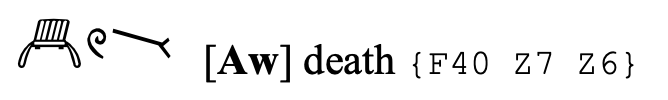

Here we see the writing of the same word - MET - with the “M owl” we know from previous lessons which shows that Hieroglyphic spelling was not fixed and could be altered by each scribe according to their preference or for practical reasons like space restrictions. We also see a depiction of a 𓁀 “mummy lying on a bed” as another determinative for Death.

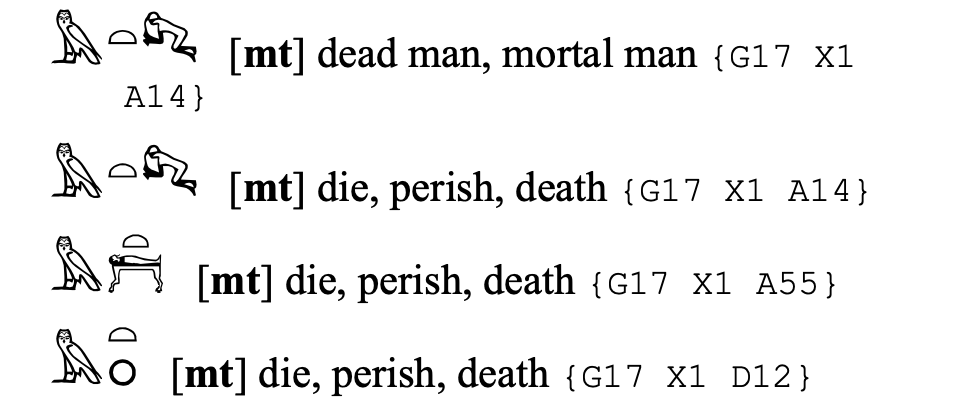

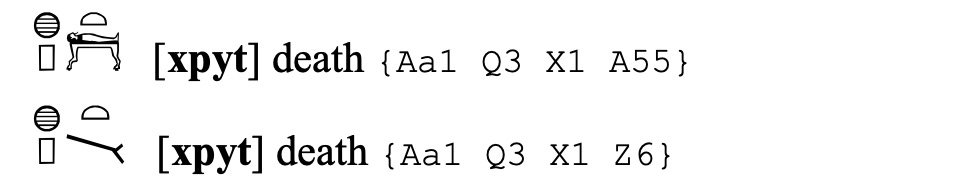

This word contains three important letters of the hieroglyphic alphabet that are important to learn. The word for death KHEPYT is spelled with:

𓐍 - Aa1: Unclassified Sign - kH pronounced as a guttural (fricative if you want) K with a hissing sound in the throat (Think Klingon “Gagh” or Swiss / German “Krach”)

𓊪 - Q3: Stool - P

𓏏 - X1: a little loaf of bread - our ever occurring buddy from lesson I. and the introduction: the T-BREAD

And the determinative is the A55: 𓁀 “mummy on bed” or the stylized Z6: 𓏱.

Metaphorical Words For Death

The abovementioned correlation between the hieroglyphic and cultural symbolism of the Ancient Egyptian language becomes apparent in their metaphorical expressions for death. Since the ancient Egyptians viewed death as a transition to the next phase of existence, and a transformative process to return from, the concept of "death" was often expressed through metaphors and verbs related to "going" or "traveling".

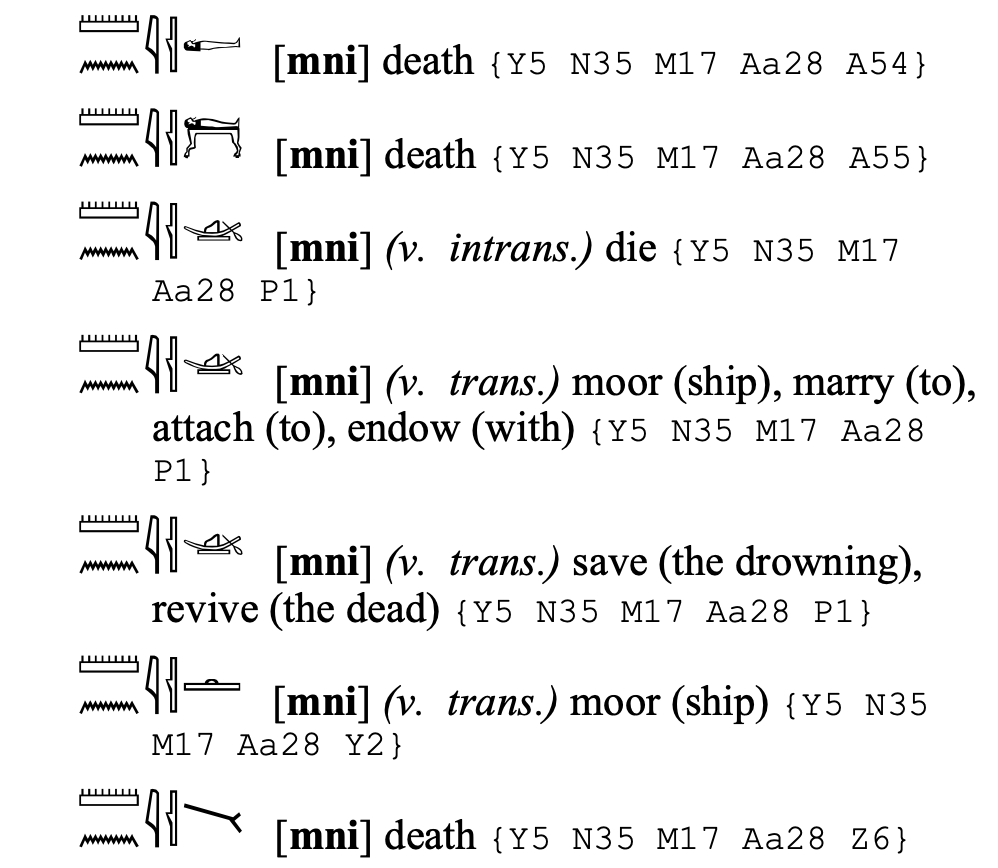

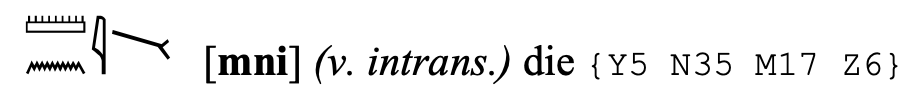

A good example is the use of the word “mooring” as a metaphor for Death.

In this word for death pronounced MENI, we have the usual “mummy” or “mummy on a bed” determinative and another two very important letters to keep in mind to improve our reading ability of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs:

𓈖 N35: water ripple - spelling the letter N

𓇋 M17: read leaf - spelling the letter I and Y when doubled (one of the few vowels that are actually written down in Ancient Egyptian)

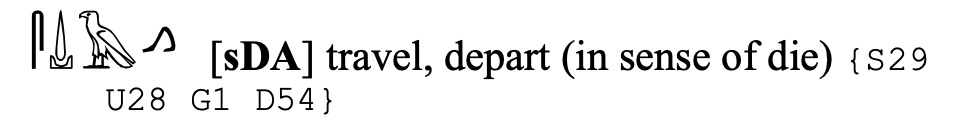

This word is pronounced SEDJA and it is written with the

𓋴 S29: folded cloth - spelling the letter S

𓍑 U28: fire drill - spelling the bilateral DJ-A

𓄿 G1: vulture or ALEPH bird - spelling the vowel A often transcribed as a 3

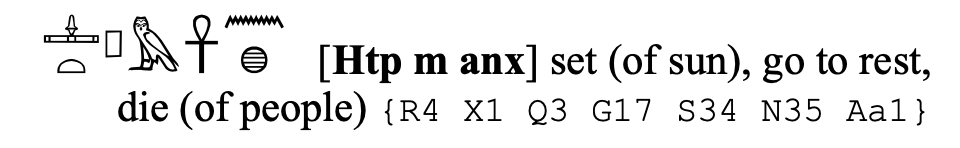

This word contains a number of important symbols and metaphors. First we notice that we already recognize the little t-bread, the p-stool, the M-owl, the N-ripple and the KH-sign (noone knows what it is but some say it depicts a placenta ?!).

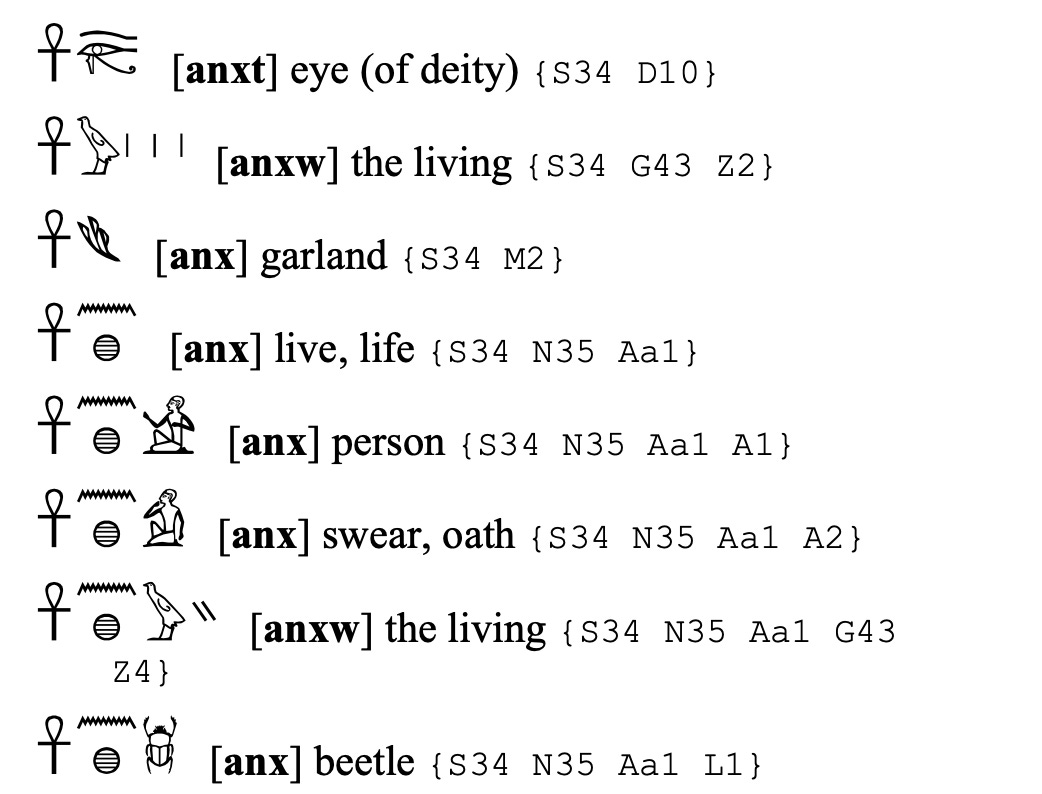

But the two most importants signs to learn in the study of Hieroglyps are of course the 𓋹 sign and the 𓊵!

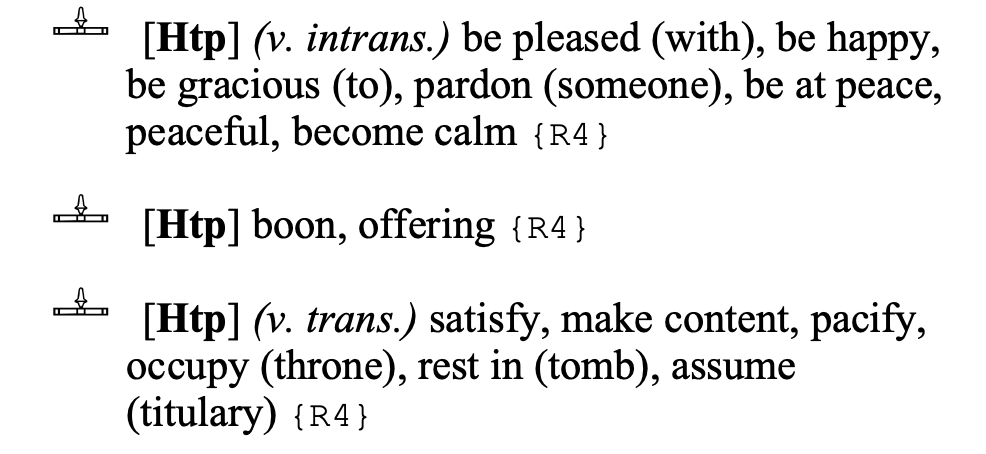

𓊵 R4: Bread loaf on mat - spelling the trilateral htp or HETEP and meaning “altar, rest, be pleased” as a stand-alone word. This Hieroglyphs is used extensively in the funerary context, for offerings and in mortuary literature. Here it is paired with the M-owl to produce the adverbial construction translating into “rest in life” aka die (we remember the last tiny grammar lesson).

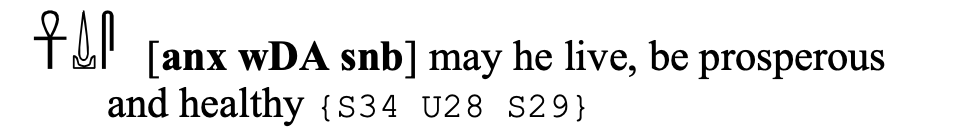

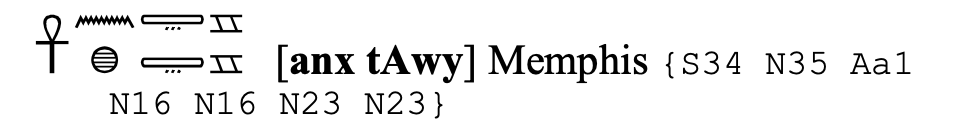

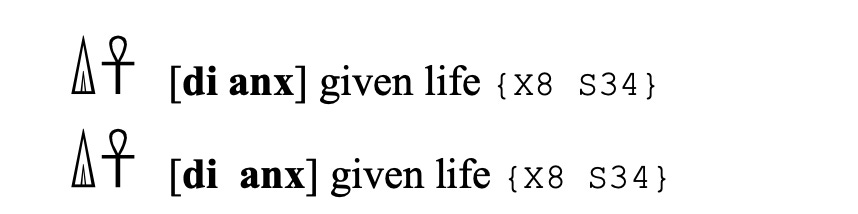

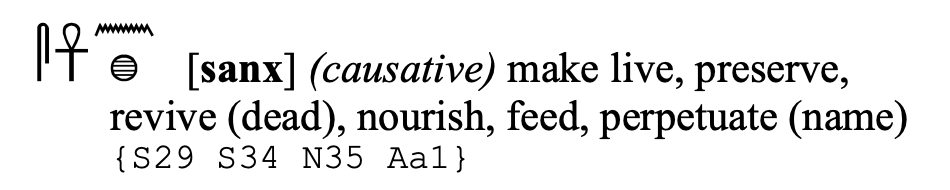

The famous ANKH sign 𓋹 meaning life is actually a sandal strap and ANKH (again with the Klingon KH sound at the end) is the one Ancient Egyptian word we have all heard before but now we know how to spell it properly (see picture below in the middle and find the N-ripple & striped “placenta”-KH along with it.

𓋹 S34: Sandal strap - spelling the biliteral N-KH

See more combinations with the Hieroglyph 𓋹 below:

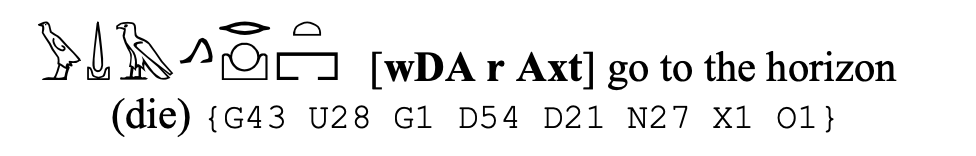

With this word - OUDJA R AKHET: die - we conclude with the last remaining written vowel we need to know, the W/OU-chicklet, 𓅱 G43: quail chick whose hieratic variation 𓏲 Z7, we have already seen above in the spelling of the word AWT and which is usually transcribed with a W but pronounced as a OU or U sound. The W-chicklet is followed by three signs we already know, the 𓍑 U28: fire drill - spelling the bilateral DJ-A and the Aleph-Bird 𓄿 G1. The two walking legs are the determinative for the word “walking or going” and are then followed by 𓂋 D21: mouth - spelling the letter R (also important and very common) it stands here for the word “to” in the verbal construct “going to the horizon” in a similar fashion as the M-owl adverbials.

The 𓈌 N27: Sunrise over mountain - spelling the triliteral 3ḫt / A-KH-T/ is followed by out little T-bread and a determinative for house, meaning “horizon” or Akhet.

Akhet is an essential Egyptian hieroglyph representing the goal of the traveling soul after death.

While the person's body remained in the burial chamber, never physically departing—but the soul -the ba - once awakened, was set free and began its journey toward a new life. Central to this journey was the Akhet: the horizon, where earth, sky, and the Duat (the Underworld) met. To the ancient Egyptians, the Akhet was where the sun rose each day, making it a powerful symbol of birth and resurrection. And it was at this event horizon where the soul traveled back - just like the sun in Ancient Egyptian mysticism - through the dark underworld and was reborn.

Modes of Being - The Soul Before & After Death

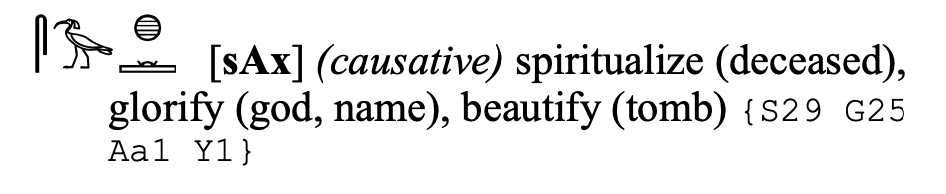

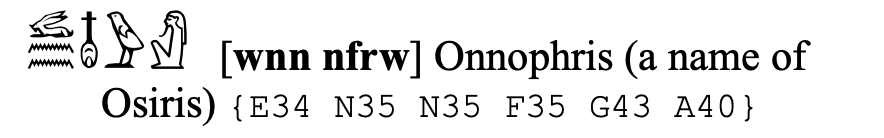

This transformation or rebirth was only possible for certain parts of the soul and those had to be transformed in the process into what the Ancient Egyptians called the “AKH” 𓅜 G25: Crested Ibis - biliteral sign 3ḫ/ A-KH meaning “spirit” —literally, an “effective one”.

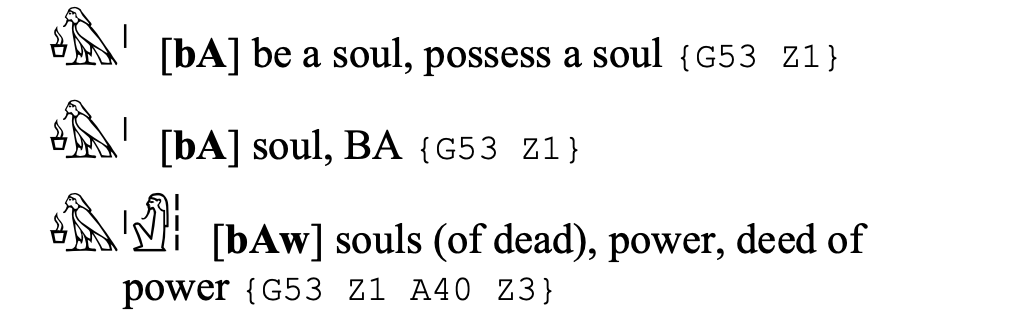

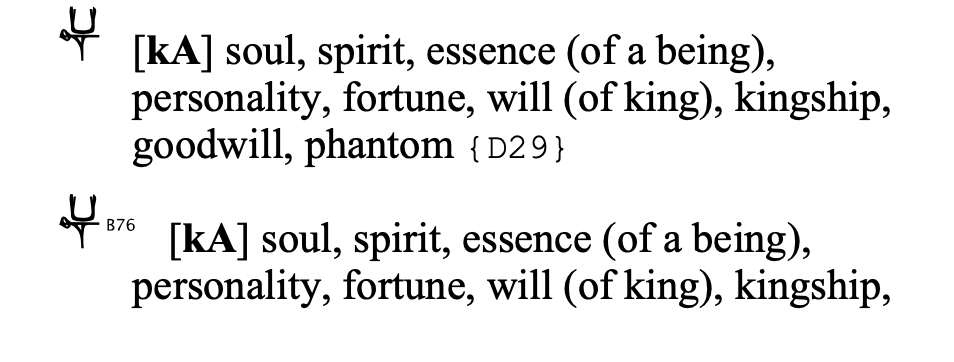

In Ancient Egypt, the "AKH" was the transfigured or blessed soul of a deceased person who had been judged by Osiris and found justified. It was a powerful, effective spirit that could still influence the world of the living. The akh was believed to need a preserved body and tomb to exist, and it was associated with intellect and light. The akh was the result of the successful union of the Ba and Ka which occurred if the person’s heart passed the test in the Hall of Judgment. Thus the primary purpose of the funerary texts and rituals was to help the deceased reunited its BA and their KA to become an AKH. Once this reunion had taken place, the deceased became able to live on in a new, nonphysical form.

The akh did not live in some heavenly paradise, but in this world, among the living. After spending the night asleep in its tomb, the akh would wake each morning at sunrise and “come forth from the necropolis” to enjoy an ideal life, free from the cares of physical existence. Because it was a spirit, it existed on the same level as the gods and shared many of the their powers.

The ceremonies performed at the funeral were meant not only to restore the dead person’s physical abilities but, more importantly, to release another soul aspect (necessary to transform into the AKH) the BA from its attachment to the body, so that it could come and go at will (see 1st picture above).

The BA was supposed to rejoin its life force (the KA, also often translated with spirit since our language cannot comprehend the complexities of Ancient Egyptian Soul lore), so that the dead person could continue to live: the deceased are often called “those who have gone to their kas.”

Before all this could happen, however, the deceased had to pass a final judgment .

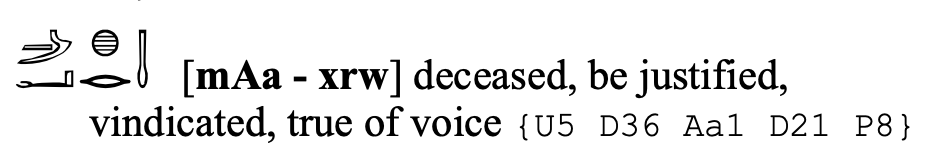

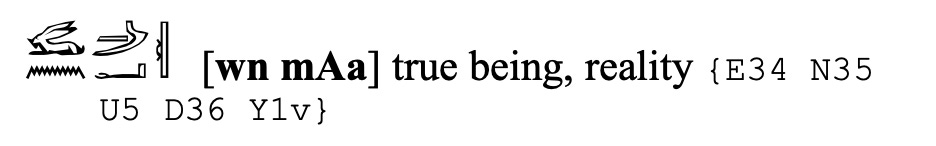

In this trial, the heart of the dead person was weighed on a scale against a feather 𓆄, the hieroglyph for m3ʿt (Maat), meaning, among other things, “proper behavior” and in other contexts “higher/divine order.” Ideally, the two sides of the scale should balance, showing that the person had lived a just and proper life. If they did, the deceased was declared “justified” (word by word “true of voice”, see below).

Here is the final half-vowel we (okay I) almost forgot: 𓂝 D36: arm - spelling a guttural a called the Ajin and preserved in todays arabic pronounciation.

Once you were anounced “justified”, you were allowed to join the society of the dead. In funerary papyri such as the “Book of the Dead,” this transition is represented in a scene where Horus, king of the living, formally presents the deceased to Osiris, king of the dead.

Tiny GRAMMAR Lesson: Negation 𓂜 NN

The concept of "death" was usually defined as "ceasing to live", or simply not-to-live

since death was after all a transition from living to non-living and to another phase of one's eternal existence. There is a grammatically easy way to denote negation in Ancient Egypt and it is written with two human arms opposite each other:

𓂜 D35: “negative arms” - spelling N or in a negation NN pronounced NEN and also doubling as a determinative for “not” or a negative in general.

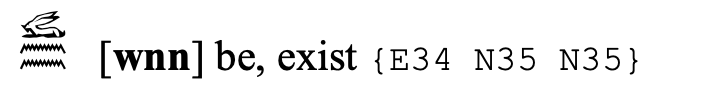

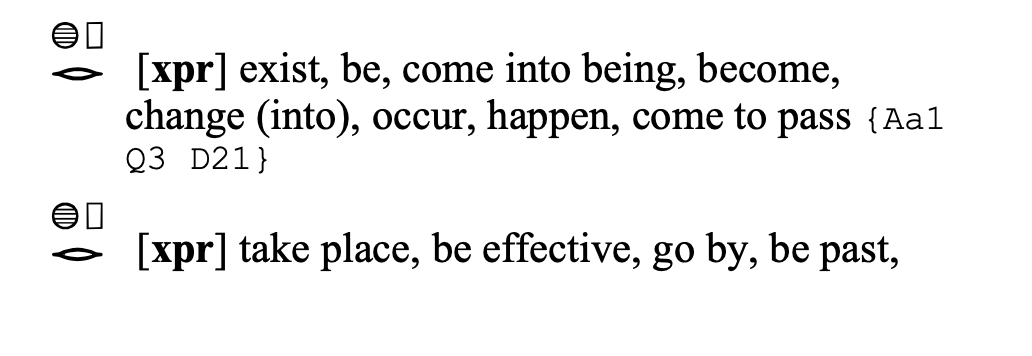

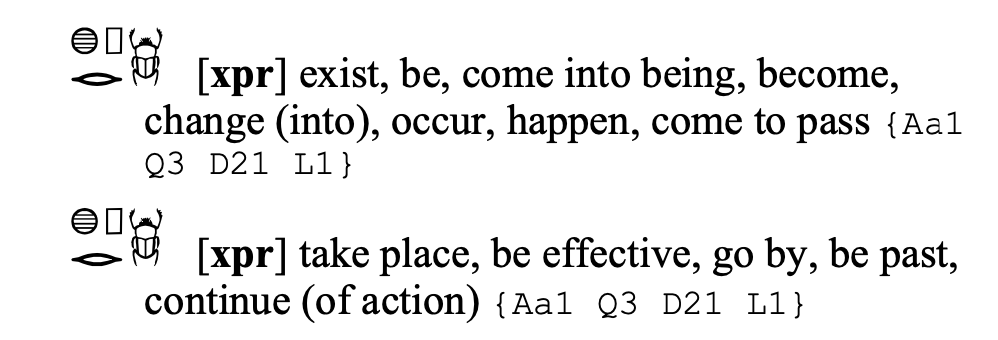

If we wanted to write ceasing to exist we would therefore take the word WNN - to be

and put the negative arms in front:

nn wnn / NEN WENEN - ceasing to exist 𓂜 𓃹𓈖𓈖

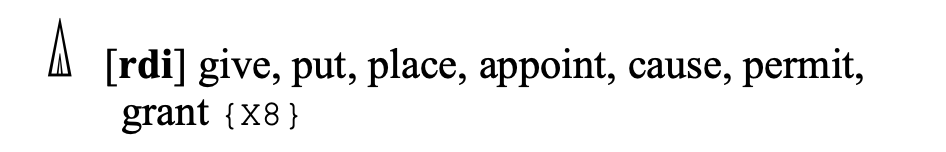

Author’s note: We made it until the end of this tour de force and by now we know all of the vowels in Ancient Egyptian, some of the most essential verbs in Ancient Egyptian, (MT to die, WNN to be, HPR to exist, HTP to rest/be at peace), two of their most important adverbials (M-owl & R-Mouth constructs) and how to negate a word OR sentence (just put the 𓂜 arms and voila!), we also learned the essential words presenting the bedrock of Ancient Egyptian mysticism and are starting to grasp the most complicated concepts of Hieroglyphic script.

𓂜 bad!

Death in Ancient Egyptian Culture

Death is not an easy topic to tackle and the tendency to gloss it over with esoteric meanderings, eager intellectualization, or ignorant contempt is strong in our culture (see Jean Baudrillard on consumerist societies’ tendency to trivialize or mock death and refuse to accept it as a part of life). So much so, that we often engage in Baudrillards “expatriation of death” without even realizing it, conveniently tucking it away in an immaterial realm, acting like the modern mind has death all figured out (at least in terms of its long-term effects and locality) to give us a feeling of control. But despite our post-enlightenment mindset towards death, the language we use to describe it is often steeped in superstitious jargon and how we choose to come to terms with death is now a matter of personal belief and by no means the affair of state religion. In short: Death - once the most profound culture generator for millennia - no longer bears any cultural or religious gravitas in 21st-century Western thought.

This stands in stark contrast to the Ancient Egyptian approach, where death very much was a matter of institutionalized state religion, with enormous resources being allocated to royal burial sites and people leaving their entire estate to temple priesthoods to ensure their ritualized caretaking in the afterlife.

The social and personal aspects of dying were also highly regulated and centralized around state religion all following the example of royalty.

In a culture that evolved around a ritualized nexus of death, the written word yielded enormous power, and the sheer proximity of Hieroglyphic spells granted protection, transformation, and eternal life.

So, the cultural importance of the hieroglyphic vocabulary to describe and depict death in Ancient Egypt cannot be overstated.

It is often debated whether proper burial and mortuary rituals were only accessible and widespread among Ancient Egyptian elites, however, Egyptologist Jan Assmann argued that even in the most minimalistic form, one can assume that the overall goals for the afterlife were modeled, copied, and adapted down to the most modest means and social strata.

With whatever means necessary or available to the individual: Death was something to be lived through, something to return from, and something to excessively prepare for and it was specific language written in their sacred script that got you from one side of existence to the other and back again.

Extra Vocabulary & Repetition/New Combinations with Existing Vocabulary

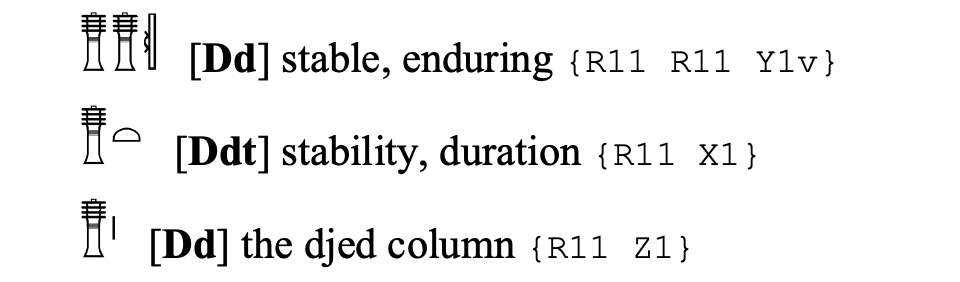

TIME & DURATION

The Djet pylon

(the symbolic backbone of the god Osiris)