Mastering Hieroglyphs: I. Breaking the Code

The mind-bending insight that led to the breakthrough in deciphering Hieroglyphic script

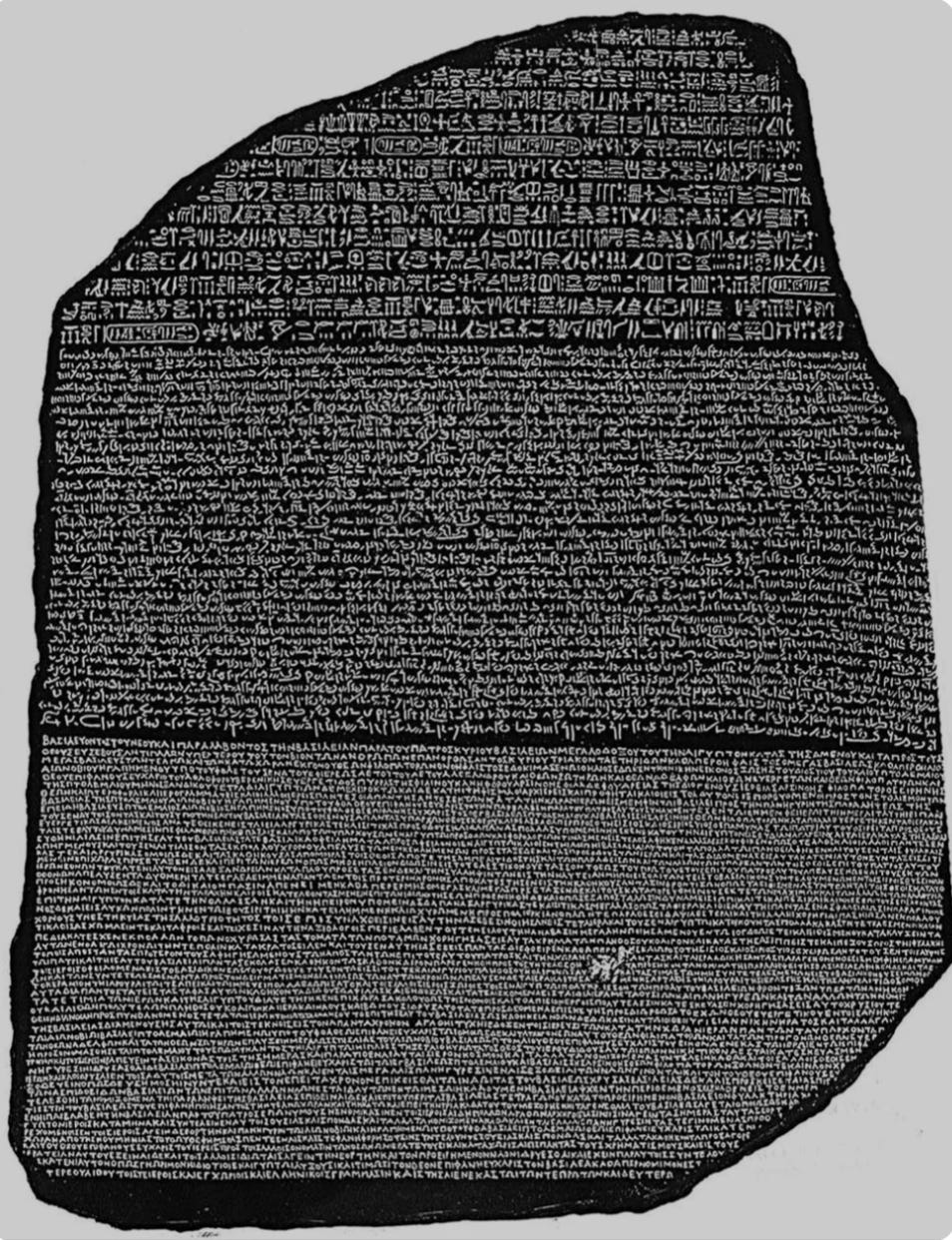

When Napoleon’s soldiers discovered the Rosetta Stone in 1799, featuring a one-by-one translation of an Ancient Egyptian decree on top of its Greek and Demotic equivalent, it was assumed that within a matter of weeks, the mystery of the Ancient symbols would finally be decoded.

However, it took another 23 years of combined scholarly effort to produce the first results that led to the final breakthrough by the French school teacher Francois Champollion.

The actual reason why the Hieroglyphic script remained “undecipherable” for 2000 years and baffled the entire linguistic community for decades, even with a Greek translation on hand, is rooted more in specific Western thinking than in the difficulty of the writing system itself, which makes the study of it an almost philosophical and truly socio-historical endeavor.

It was long assumed that hieroglyphs recorded ideas and not the sounds of the language, and many attempts were held back by a belief in the mystical nature of the symbols. In contrast, others believed it was a mere logographic system similar to written Chinese.

While both of these theories were true in some regards, other than solely logographic systems (a writing system where each character represents a whole word or meaningful unit), Hieroglyphic script consists of a logophonetic writing system, combining symbols for words and sounds - for instance, the little floating “t-bread” 𓏏 - as in the word for Bee or King of Lower Egypt pictured below - denotes the letter T without any deeper meaning or symbolism. At the same time, the word for bee is also written with a bee symbol. Still, the same symbol can also be a part of the word for King of Lower Egypt (BITY) and at the same time stand for the logographic pronunciation BIT as a logograph of the word for king without losing its symbolic meaning (bees were a metaphor for royalty).

And herein lies the key problem to deciphering this script: some Hieroglyphs can be pictographic, ideographic, logographic, and alphabetic simultaneously.

The same goes for the scarab hieroglyph: it is a pictograph for the word scarab but also a logograph for the word form/shape, touching upon its metaphorical aspects of the dung beetle as a symbol for “coming into being” (since it buries its larvae within a dung ball in the sand and the young beetles appear seemingly out of nowhere).

Signifiers & “The Rebus-System” - Meaning and Sound Intertwined

As we see in the words for King of Lower Egypt and the Scarab (pictured above), the Egyptians not only used so-called Ideograms (when the symbol depicts the actual object, denoted by a little vertical line) and letters like the t-bread 𓏏 (see Ancient Egyptian Alphabeth pictured below), but they also employed a sort of Rebus system, where a symbol denoting a word can become part of another word. For instance, the bee, which reads at BIT, becomes part of the word for King of Lower Egypt in combination with the t-bread and a Signifier, a seated figure wearing the crown of Lower Egypt, pronounced BITY.

In the word for beauty (pictured below) spelled NFR, we can see the Rebus principle at work again: an Ideogram (heart & lungs) pronounced NFR (Three-Consonant Sign) is accompanied by the horned viper, an alphabetical sign for F and the mouth, alphabetical for R. While it seems counterintuitive for a highly symbolic writing system to double down on its spelling, these alphabetical signs often help in the pronunciation of words (and help distraught language students in identifying lesser-known signs), and they also held the key to making the first (failed) translation attempts in the early 18th century.

To make this even more confounding, Hieroglyphic writing uses close to 800 different symbols, some of which can be used in multiple ways: as an alphabetical letter (see chart below), an ideogram (like the Scarab), a signifier (denoting the meaning of the word) and a phoneme/logograph (using the sound of a word to spell up to three consonants in one sign, like the HPR sound of Scarab as part of another word), and all of these principles can be combined in a single word.

The key realization that led to their decipherment was that Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs could be many things at once: sound, mystic symbol, alphabetic letter, and logogram.

The Ambiguity of Hieroglyphic Script

The ambiguity of meaning in the Ancient Egyptian writing system not only baffled its translators but also emblematized the conceptualization of their world, which is best exemplified by the words and expressions surrounding the heart.

The Heart As Signifier, Metaphor, Symbol, and Metaphysical Concept

The hieroglyph for the heart is written like this: 𓄣 - a symbol or ideogram depicting the word for heart (pictographically), which also appears in words revolving around more profound or abstract formulations the Egyptians believed to be seated in the heart, like morality, decision making and consciousness.

The actual word for the physical organ, however, is written with the forefront of a lion 𓄂 (heart in Ancient Egyptian is pronounced ḥ3ty and the lion stands for the letters ḥ3t, accompanied by the t-bread and the heart acts as a signifier here), and the above-mentioned symbol functions as a so-called signifier (see picture below for hieroglyphic spelling).

The lion forefront is also linked to words meaning the foremost, the finest of, and the beginning, further drawing from animalistic symbolism to underline the importance of the heart in Ancient Egyptian thought, which was believed to be the seat of every human’s capacity for understanding, desire, moral reasoning and - most strikingly - thinking (as history channel watchers know, the brain was not considered of any consequence and was discarded in the mummification process).

When the heart hieroglyph stands alone and is not further specified, it therefore embodies all these metaphysical, cognitive, and psychological aspects of meaning at once:

But once it is used as one element of a word, it can also denote an abstract metaphor for being “at the heart of” something

or, as it appears in the spelling of the adjective for pleasing, it can be part of a metaphysical metaphor blending the physical with the abstract, denoting the human faculties needed for perceiving and emanating beauty (nfr) as the face 𓁷 (Hr) and the heart 𓄣(ib):

The Key to Deciphering Hieroglyphs

Now that we have digested the Rebus System, the Alphabet, and the Signifiers, we can go one step further and look at the Cartouche that held the key to deciphering Hieroglyphs.

If you followed the examples above, you can already translate several words here:

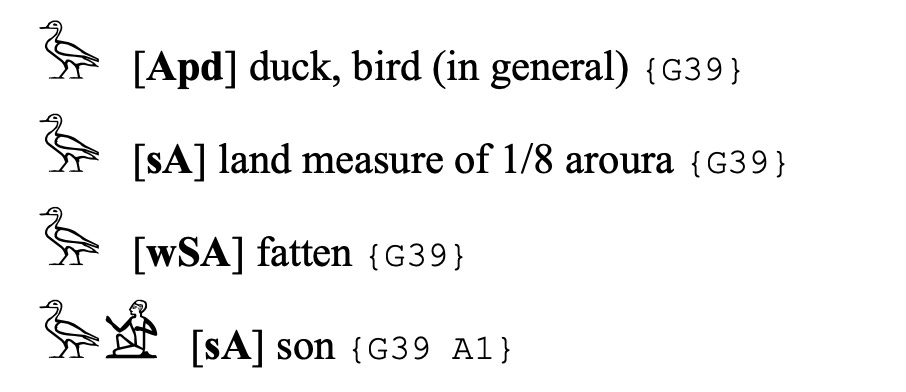

The bee and the t-bread stand for King of Lower Egypt and are part of the pharaonic titular n(j) + swt + bjt, literally ‘the belonging one of the sedge and of the bee’ (W is the transcription for a U or OU sounds in Ancient Egyptian) - you will also recognize the duck (meaning son). Since the little circle with the dot is the sun, which can either signify the sun god RA, stand for the word day, or function as a stand-in for the phoneme (two letters in this case) RA, it translates here to: Son of Ra.

It was through the spelling of the name of Ramses II that Champollion was led to his most significant breakthrough in understanding the multi-faceted use and ambiguity of the script that had confounded scholars for millennia.

He realized that Ramses sounded out as RA-MES-SU in Ancient Egyptian, used the Sun Hieroglyph as a phoneme for RA, the MES bundle (see picture below) as a phoneme, and a Three-Letter-Consonant sign, and the folded cloth as the alphabetical letter S (see chart with Ancient Egyptian alphabet above), which is repeated in the sedge Hieroglyph SW.

The recognition and spelling of this name led to the realization that the attempts to pin the writing system down to one defining principle (Pictogram, Alphabet, OR Logogram) had been in the way all along. Once translators like Champollion overcame the Western penchant for rigid categorization and fully embraced the Ancient Egyptian principle of intentional ambiguity, they finally succeeded in deciphering Hieroglyphics and the Ancient Egyptian language. This breakthrough took almost two millennia and paved the way to understanding one of the most mysterious and long-lasting cultures known to us.

Carla,

You had me at Archaeology—the science of ourselves! I cannot wait to explore your site, and I'm writing to you to express my excitement about finding it!

Oh. Come to think of it. You found me first by subscribing to my site.

Joel